Her story.

We will be sharing more of Brighton’s story in time but wanted to share the following moments for those who want to learn more about her.

Pregnant!

In April, we were blessed to learn we were having a baby due in January. By June, it wasn’t quite time to announce it yet, but we were so excited to have our mothers with us as we found out we were having a daughter, and naturally went and bought a few dresses. Within a few weeks were were talking about names and debating how we wanted to get ready for our little girl.

Diagnosed with CDH

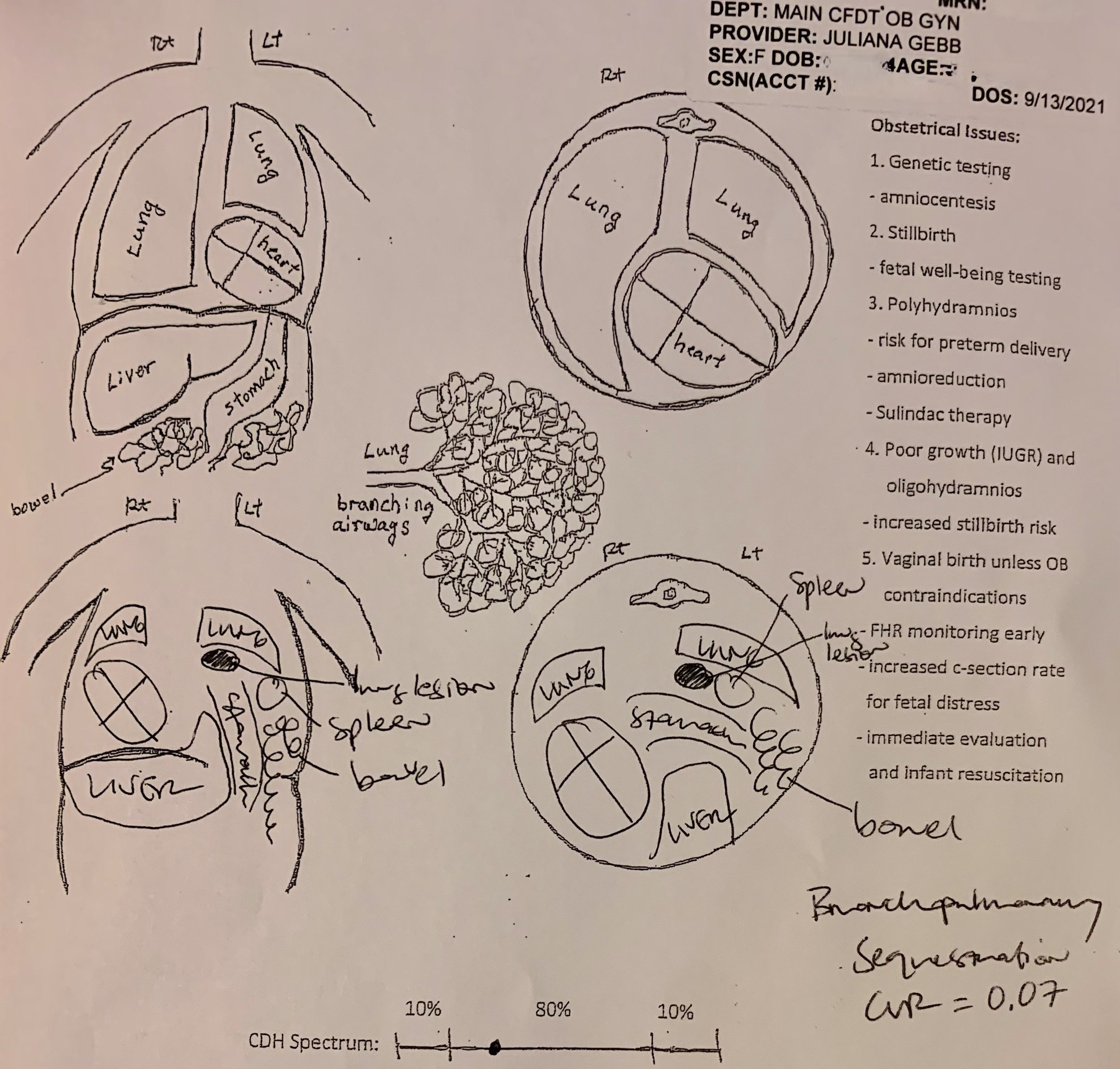

In August, barely past the first trimester, at a routine ultrasound, the sonographer got quiet and was taking longer than normal. Our doctor told me it looked like our baby had a diaphragm defect but it was really rare and she couldn’t tell for sure. She got on the phone and got us an appointment with a Maternal Fetal Medicine specialist the next morning. In less than 24 hours, we learned our baby had Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia (typically just called “CDH”). This meant her diaphragm was not fully developed and abdominal organs like the stomach and intestines had moved into the chest, blocking the growth of her lungs. It’s a condition that affects about 1 in 3,000 babies, similar to conditions such as Cystic Fibrosis but is far less well-known. If you google CDH, the first scary statistic is that it has a 50% survival rate and many hospitals recommend termination. But, with good medical care, survival odds are typically as much as 85%, and quality-of-life prognosis tends to be optimistic.

We spent the next few weeks researching and learned that they don’t know why CDH happens. It’s often paired with other genetic issues so we took every genetic test out there but everything came back clean. So she has this life threatening condition, but is otherwise perfect. We started to see that everything about this was going to be different. Seeking help, we discovered the sometimes-helpful and sometimes-maddening world of Facebook support groups, which we can discuss some other time. Our priority was finding the best care possible for our baby and that meant consulting at hospitals all over the country. We had barely started telling friends and family we were having a baby, and now the news came with a huge asterisk. More often than not, we were silent which is why many of you probably didn’t even know we were pregnant.

Over the next two months, we consulted at hospitals in San Francisco, Philadelphia, Houston, Seattle, Los Angeles and St. Petersburg FL. Treating CDH is not simple. Here’s a little of what we learned…

-

So. Much. Travel.

This became an every week sort of thing. Last minute flights, buying tickets in Ubers. Cancelling on work things. Dropping off the dogs. So much support from our family and work family for holding us up, thank you.

-

Tests on Tests on Tests

Ultrasounds, echocardiograms, MRIs, over and over, and over. And each time, it just feels like everyone is looking for something else to be wrong.

-

What about the Hospital?

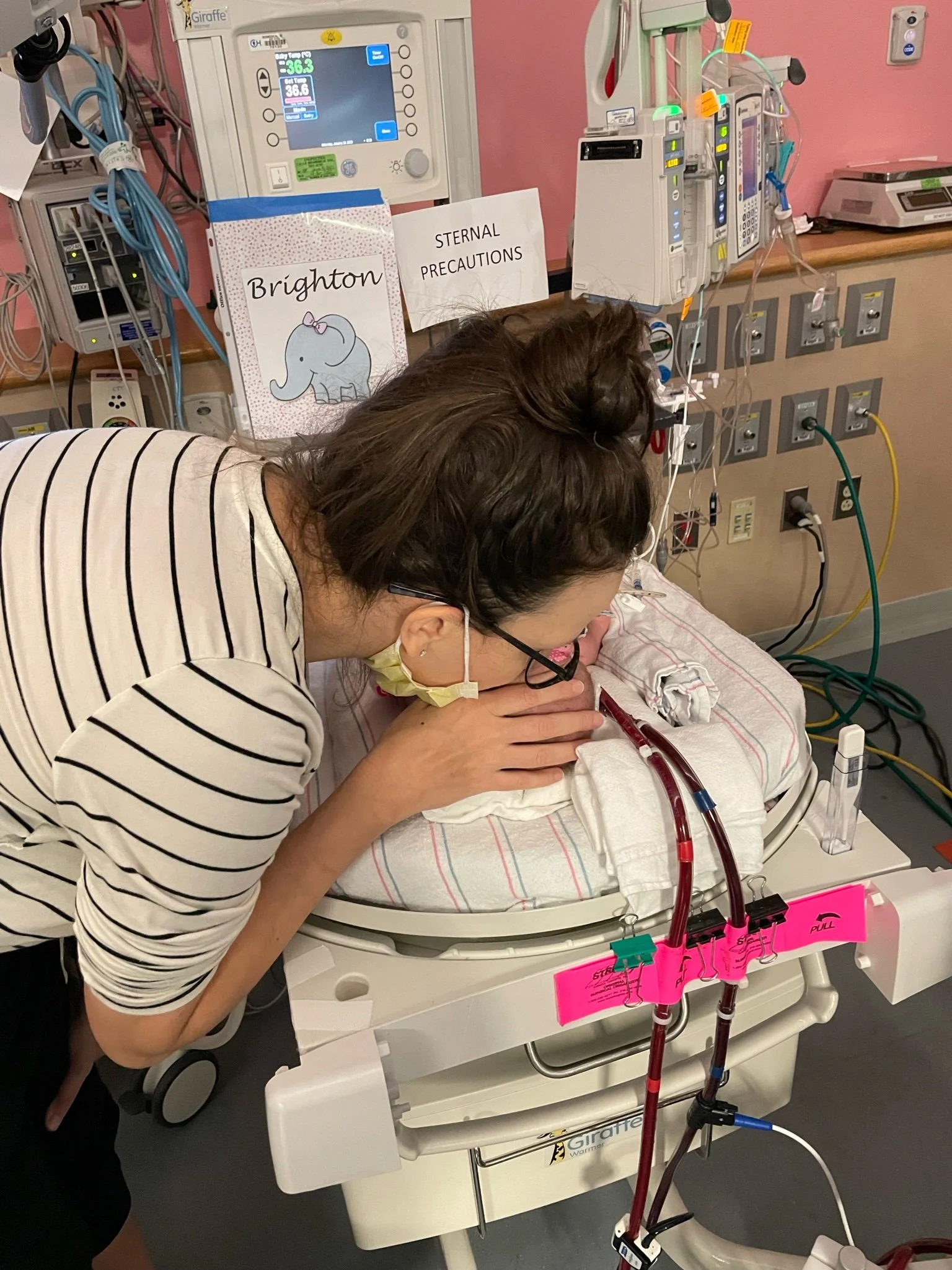

Babies need immediate attention after birth to support their lung function. No holding, no baby on the chest, nothing. It’s too risky. So a major children’s hospital at a research institution with a Level IV NICU.

-

So She'll Need a Surgeon

While it’s not an incredibly complex surgery, it’s still surgery on an infant. What’s their approach - gortex patch, muscle flap, laproscopic, incision, silos? And how much experience do they have with CDH?

-

Neonatologists and the NICU

They’re in the trenches for months - both leading up to and after surgery, slowly adjusting so babies can breathe without a ventilator. And what about the bedside nurses and all the other specialties?

-

Do we qualify for FETO?

Oh wait, there’s risky in-utero surgery called FETO where they inflate a tiny balloon and put it in your baby’s mouth. But only some hospitals do it and your case needs to be dire enough to qualify.

-

Who's Delivering the Baby?

Meet the MFM team who delivers the baby. Do they induce and at what week? Some induce as early as 35 ranging up to 39. How quickly do they turn to c-sections? Will I even meet my doctor?

-

Trusting Your Gut

Most places during consultations you meet a surgeon, an MFM and some nursing staff. And you’re still trying to understand the diagnosis. There are so many more people who are part of this and you have to go off feel.

-

Where Will We Live?

Are there Ronald McDonald Houses? Short term housing? Can we get around? How far will we be from major airports? Can we handle the weather?

Baby Girl on the Ultrasound in Texas

City Hall in Philadelphia

In Philadelphia at CHOP

Liberty Bell in Philadelphia

Texas Children's in Houston

Bumping

Off to consult at Texas Children's

Hi little one at Texas Children's

Back at the airport, double masking

At the airport in Tampa

Local street art in St. Pete

Early early morning breakfast before leaving Florida

In St. Petersburg, Florida at JHACH

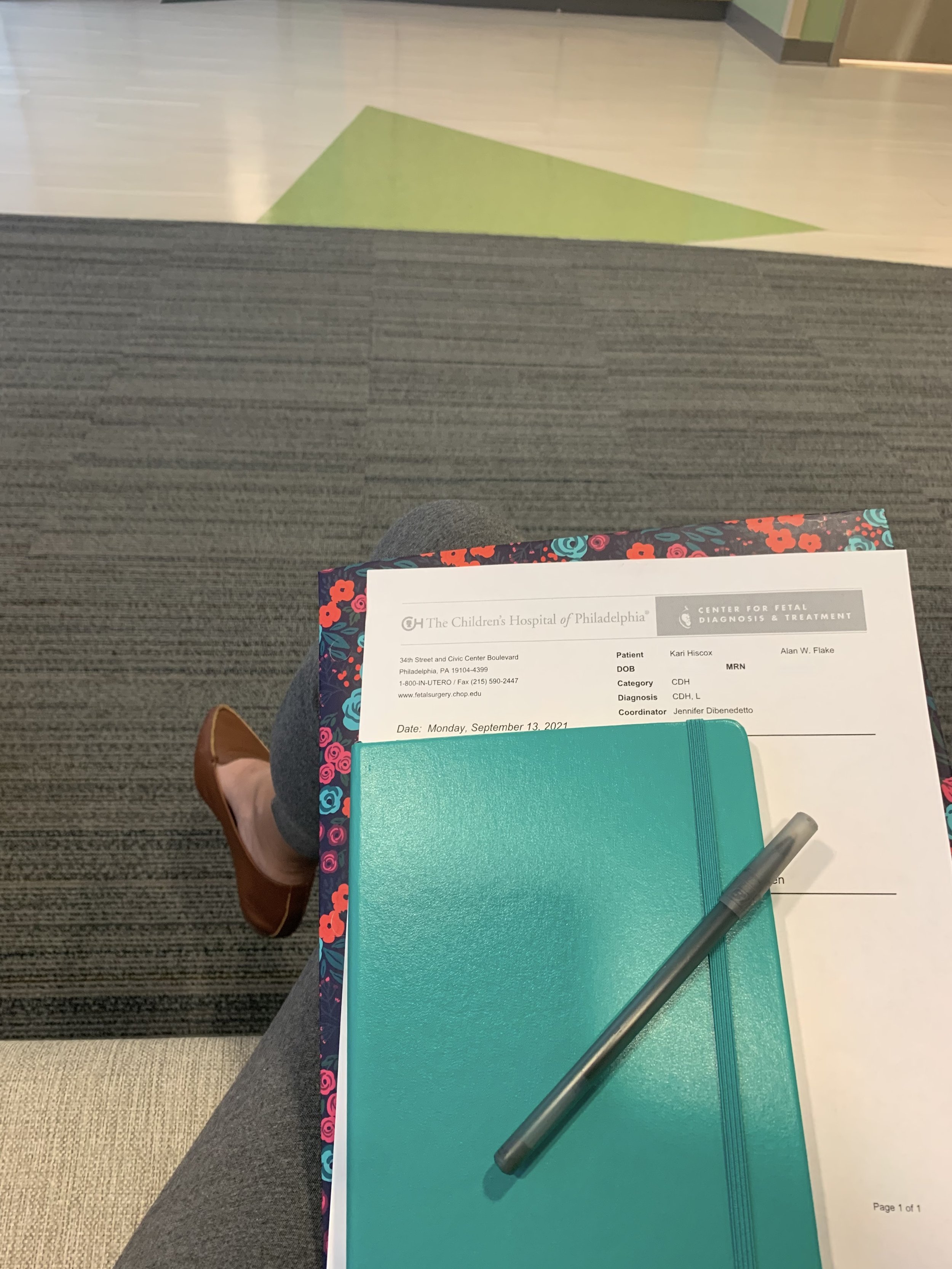

CHOP - Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia

This wasn’t just about finding just a good surgeon or just a well-rated hospital with a Level IV NICU. We considered many great options, but after everything we felt most comfortable going to the Special Delivery Unit at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (affectionately referred to as “CHOP”).

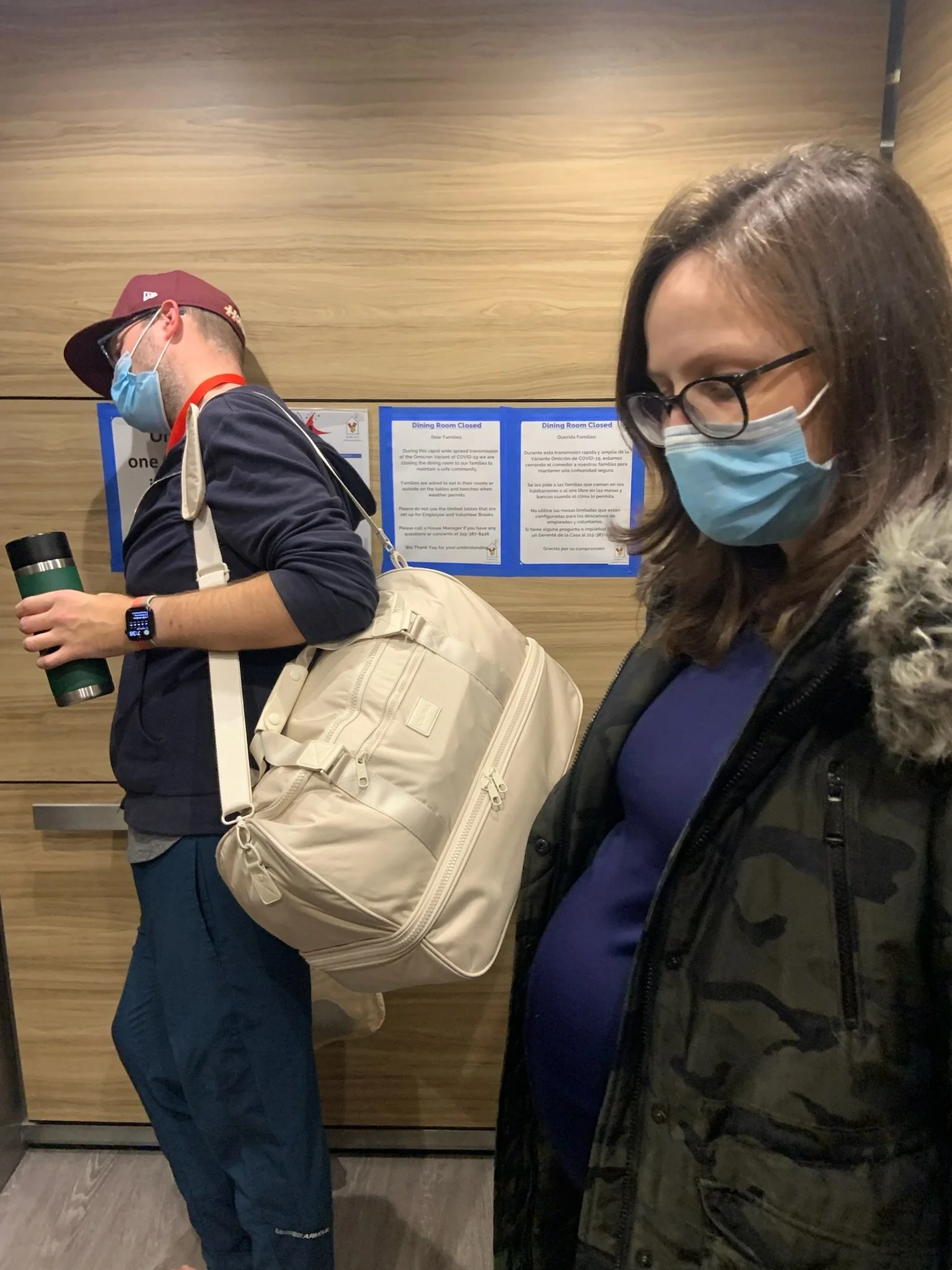

We packed up everything in our Santa Monica apartment, hugged our dogs Holly and Chubby goodbye and relocated to Philadelphia in early December, moving into the Ronald McDonald House on Chestnut Street, just next to the University of Pennsylvania and about a mile from CHOP. Over the ensuing month we attended our usual appointments at the hospital, resumed discussing baby names, and generally just spent the holidays getting excited and nervous for the baby to come.

We’re Going to Have a Baby Today…

Nope, Tomorrow…

Nope, the Next Day.

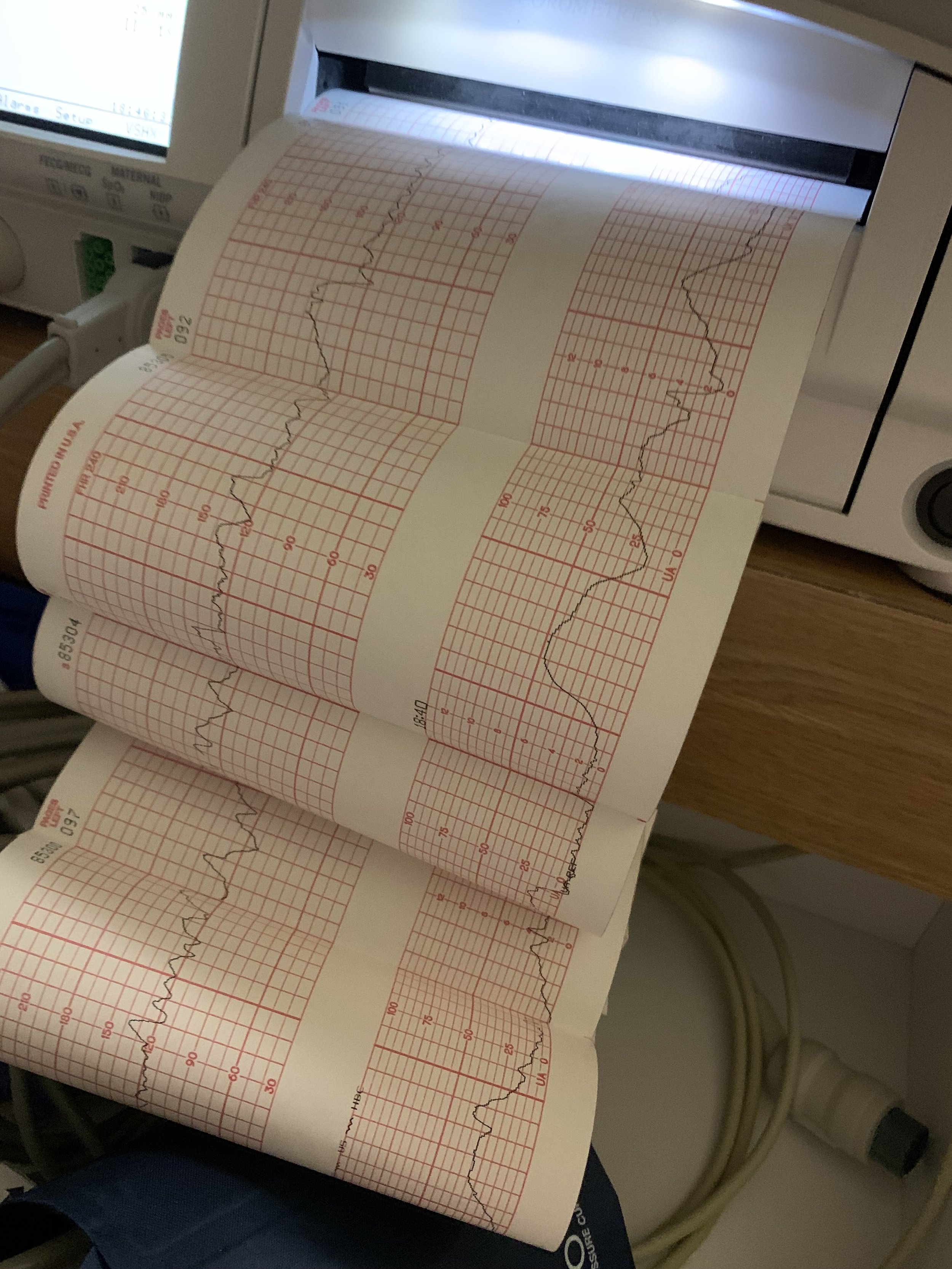

At 39 weeks, we packed everything up and left for CHOP on the evening of January 5. The hospital wants to make sure the baby has immediate medical attention after birth, so inducing labor was a necessity. So the waiting game began. Despite continuously increasing medication to induce labor, the baby was perfectly happy where she was. After two full days, the OB broke Kari’s water to get things moving.

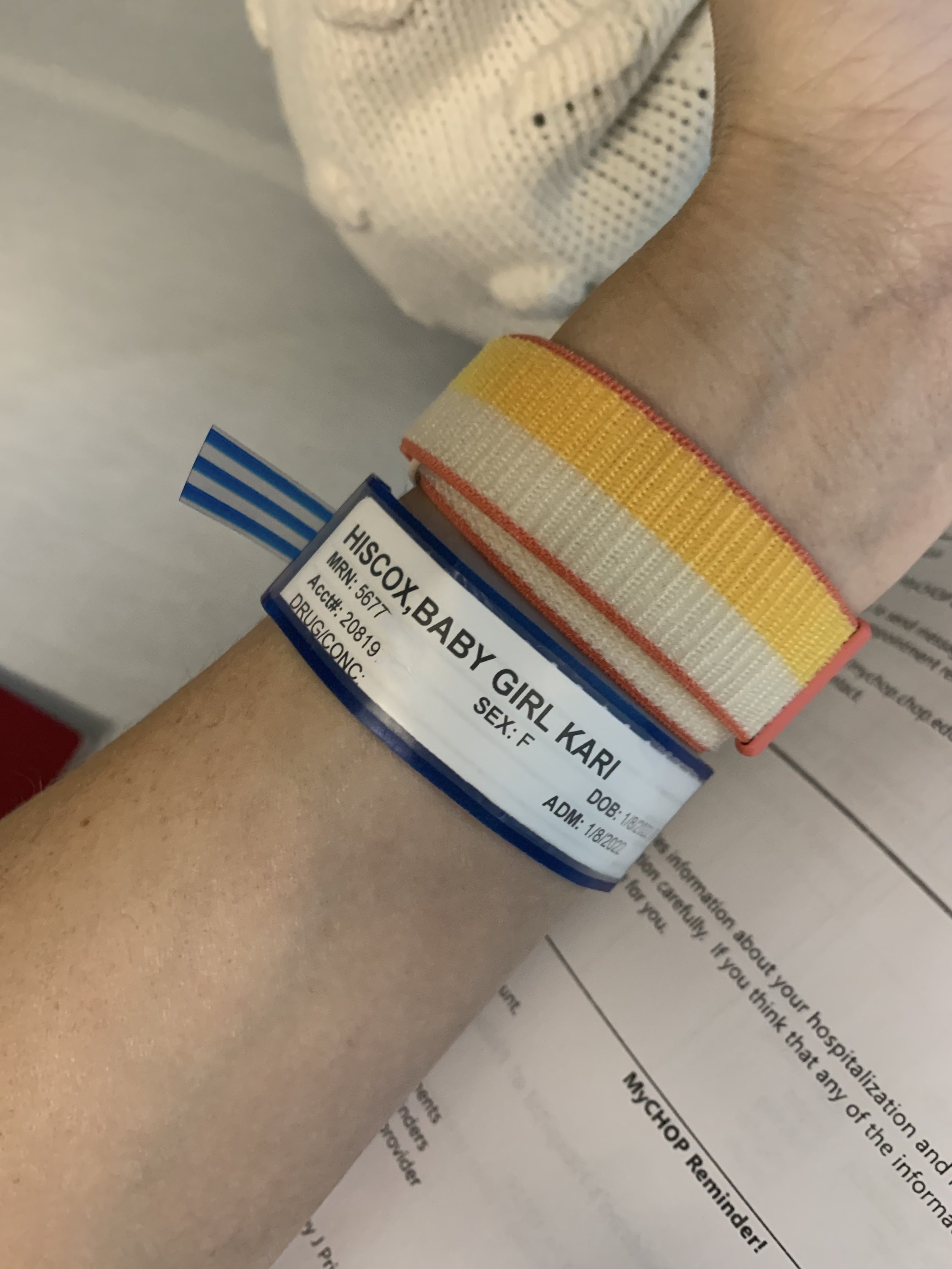

On Saturday, January 8th at 1:09pm, Kari gave birth to a beautiful baby girl weighing 6 pounds and 13 ounces and referred to as “Baby Girl Hiscox” as we hadn’t picked a name yet. The doctor held her up for just a moment, time to cut the cord and she made a gargling noise for us. After that she was rushed through a window into a stabilization room adjacent to us where she was intubated and stabilized over the next two hours. They brought her in to see us for just a moment and then took her to the NICU.

The First 24 Hours

After about 6 hours, we were notified that the baby needed ECMO. This was not going to be a typical CDH course - ECMO is effectively a version of life support and while not unusual for CDH patients, it’s for more severe cases. We knew this could happen and were relieved that the procedure to get her onto ECMO, which is significant, was successful. Unfortunately, not even 2 hours later, the surgeon was back in our room telling us the baby had unusual fluid buildup around her heart and would require exploratory surgery immediately and that she was in critical condition. They suspected she may have a perforated heart or an undiagnosed defect and her life was in danger.

After a tense couple hours, the chief of cardiac surgery called to let us know they did not find anything wrong with her heart, though they remained a bit confused about the fluid buildup. We were relieved momentarily and the doctors all said she’d returned to being “cautiously stable.” She had a long road ahead but after an intense first 24 hours, she had begun to settle into her treatment and we could start thinking about a future. We hadn’t even given her a name yet!

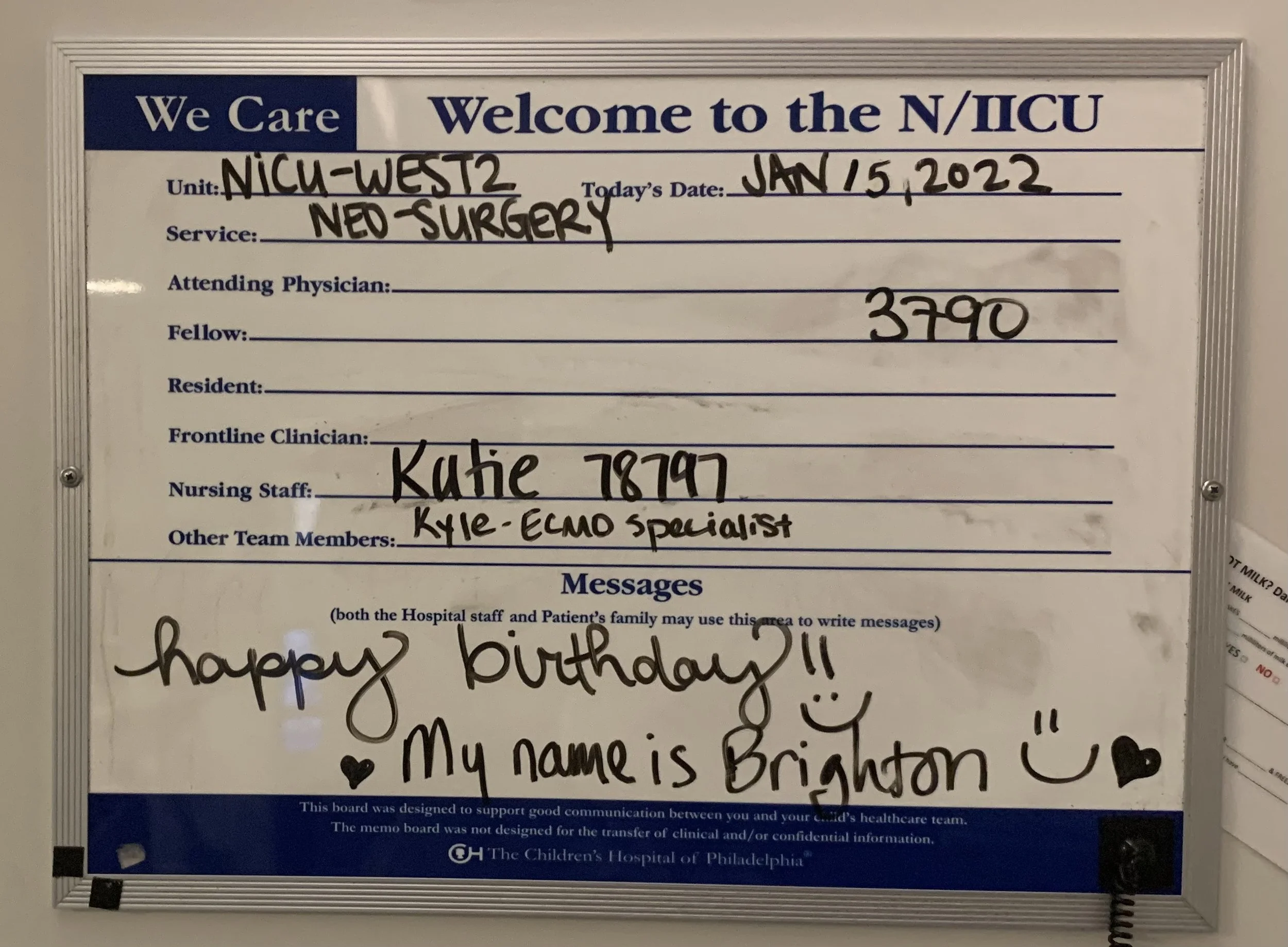

We started with 100+ contenders and slowly whittled it down, and after spending time with her, it just felt right. We named her Brighton Emmaline Hiscox Wade on Monday, January 10th. We went down to the NICU, wrote her name on the whiteboard, told our nurses and prepared for what we expected to be a multi-month stay in the NICU.

The Next Two Weeks

The first week in the NICU was mostly an educational process. Meeting the nurses and larger medical staff, attending rounds, and simply trying to understand what our day-to-day might look like. We were warned about burnount for parents in the NICU so we attempted to take that to heart and make sure we balanced our time. Meanwhile, Kari had just given birth and was pumping every two to three hours and needed time to recover.

Unfortunately, Kari wouldn’t get much time before she was back in her own hospital bed. We will walk through that story separately, but Kari spent most of Brighton’s second week of life next door at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania recovering from a major hemorrhage (technical term: Vessel Subinvolution of the Placental Implantation Site), which left her with a dangerously low blood count and in need of numerous blood transfusions and regular supervision. We were fortunate that it happened while we were at CHOP visiting Brighton and that she was surrounded by medical personnel, notably a nurse that quickly and clearly identified what was going on and mobilized a team, and ultimately Kari was able to physically recover.

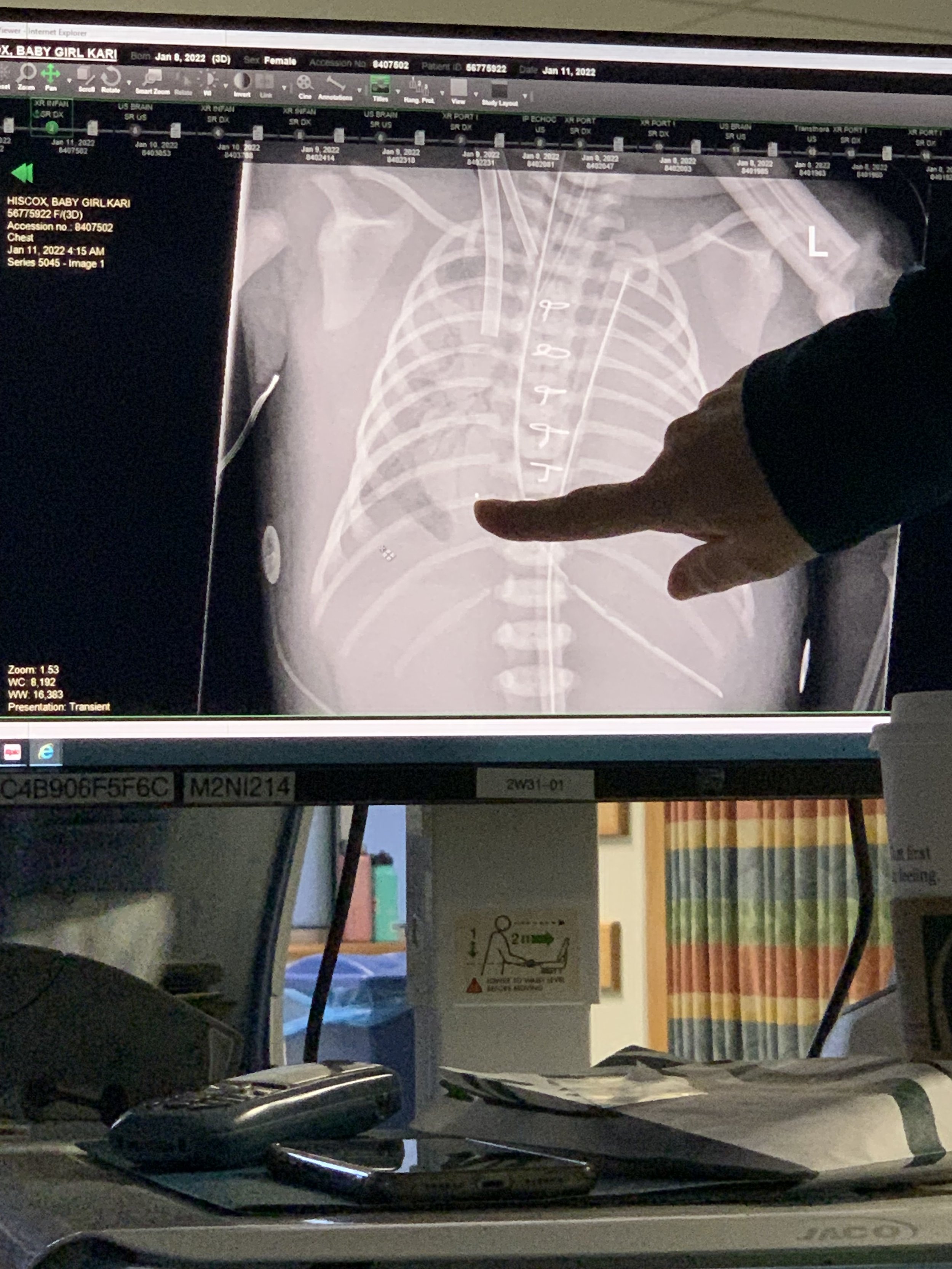

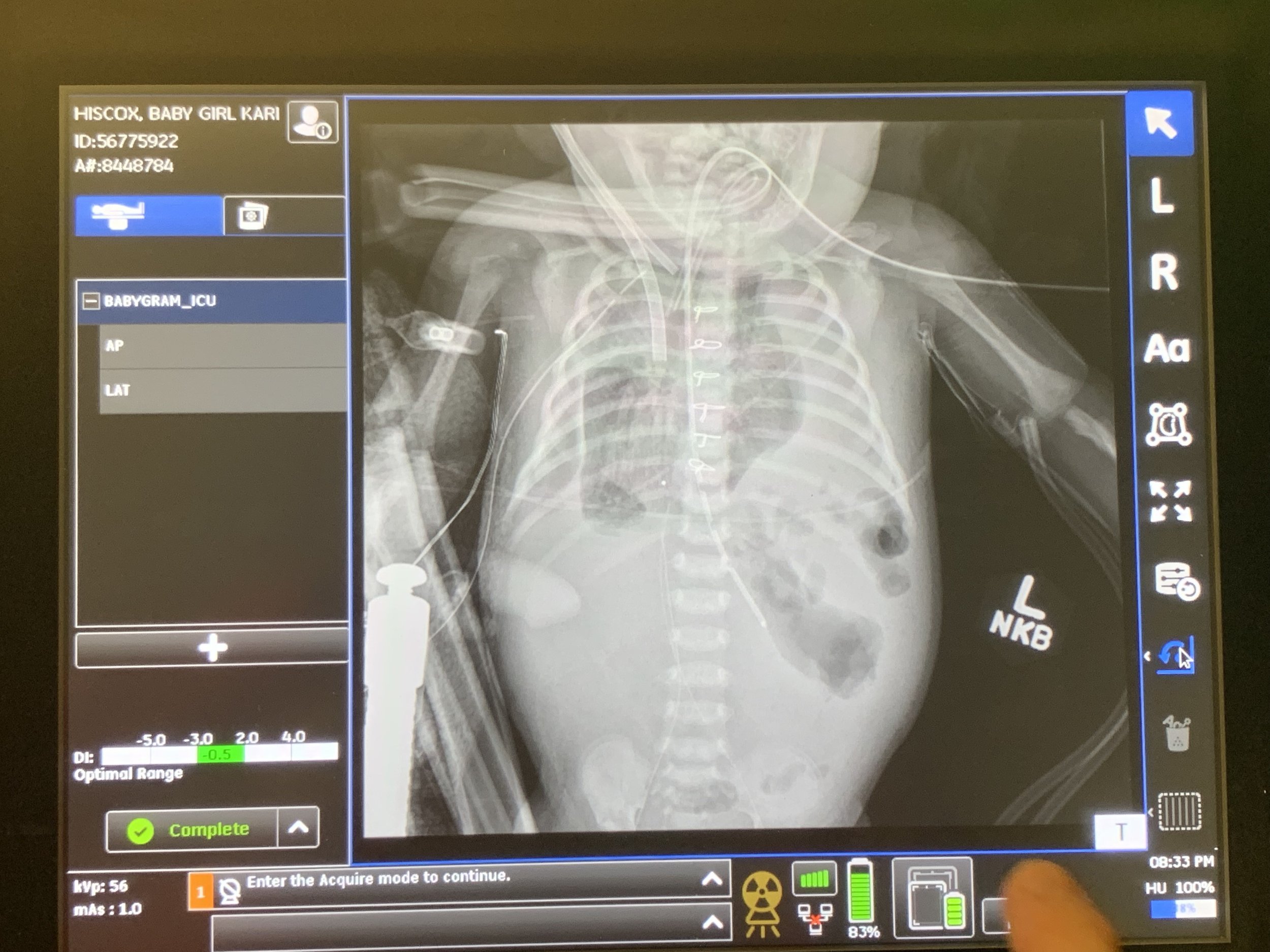

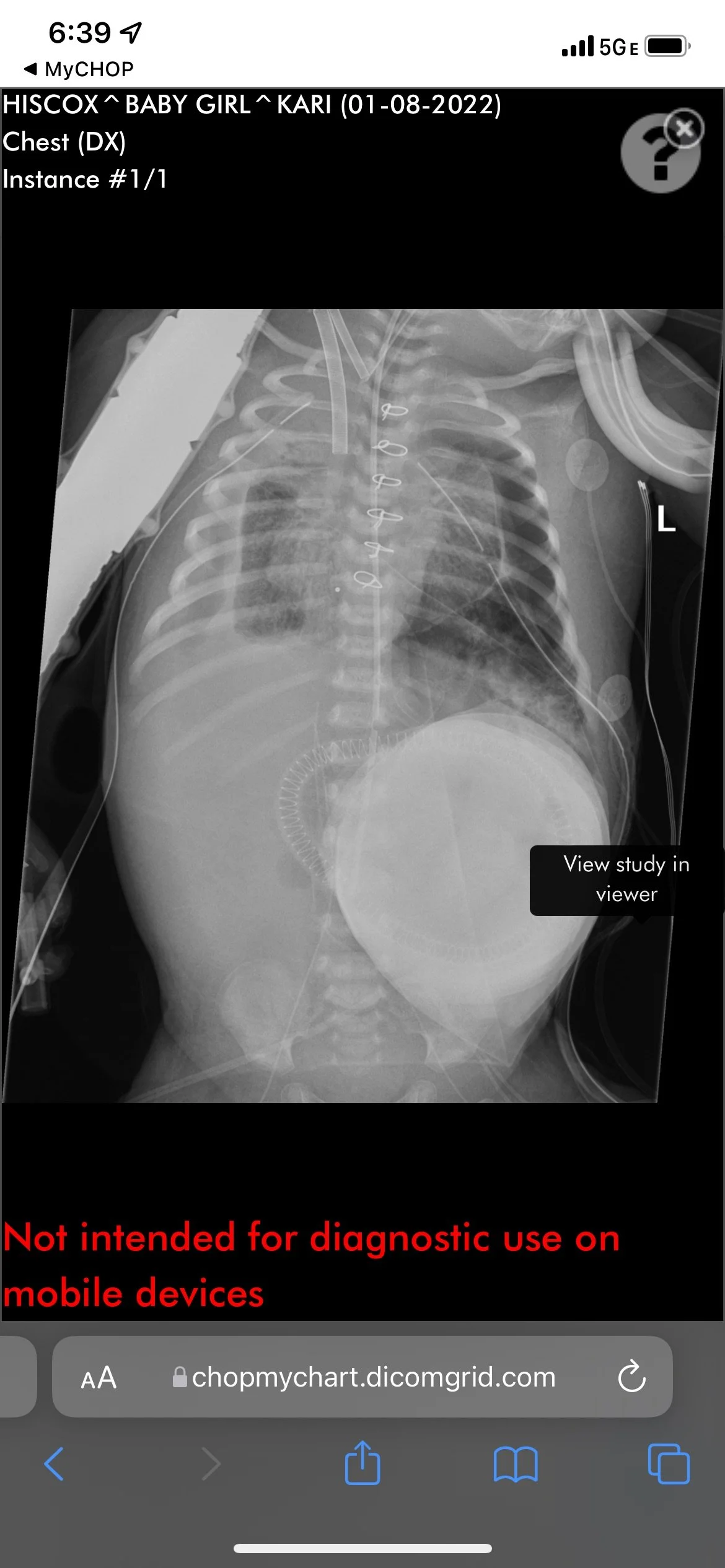

Her Progress on ECMO

Over the coming weeks, we spent hours by Brighton’s side in the NICU reading to her, getting to know her bedside staff, trying to take occasional small excursions out into Philadelphia (mostly for sandwiches at Middle Child), but were also starting to get anxious about her progress. Babies with CDH typically have their repair surgery within the first week or two of life, and it’s not good to stay on ECMO for more than a couple of weeks. We became hyper-focused on her chest x-rays which were “whited out” and not showing any open lung. Brighton was stable as long as she was on ECMO, but very sick. And ECMO is not something people can last on forever.

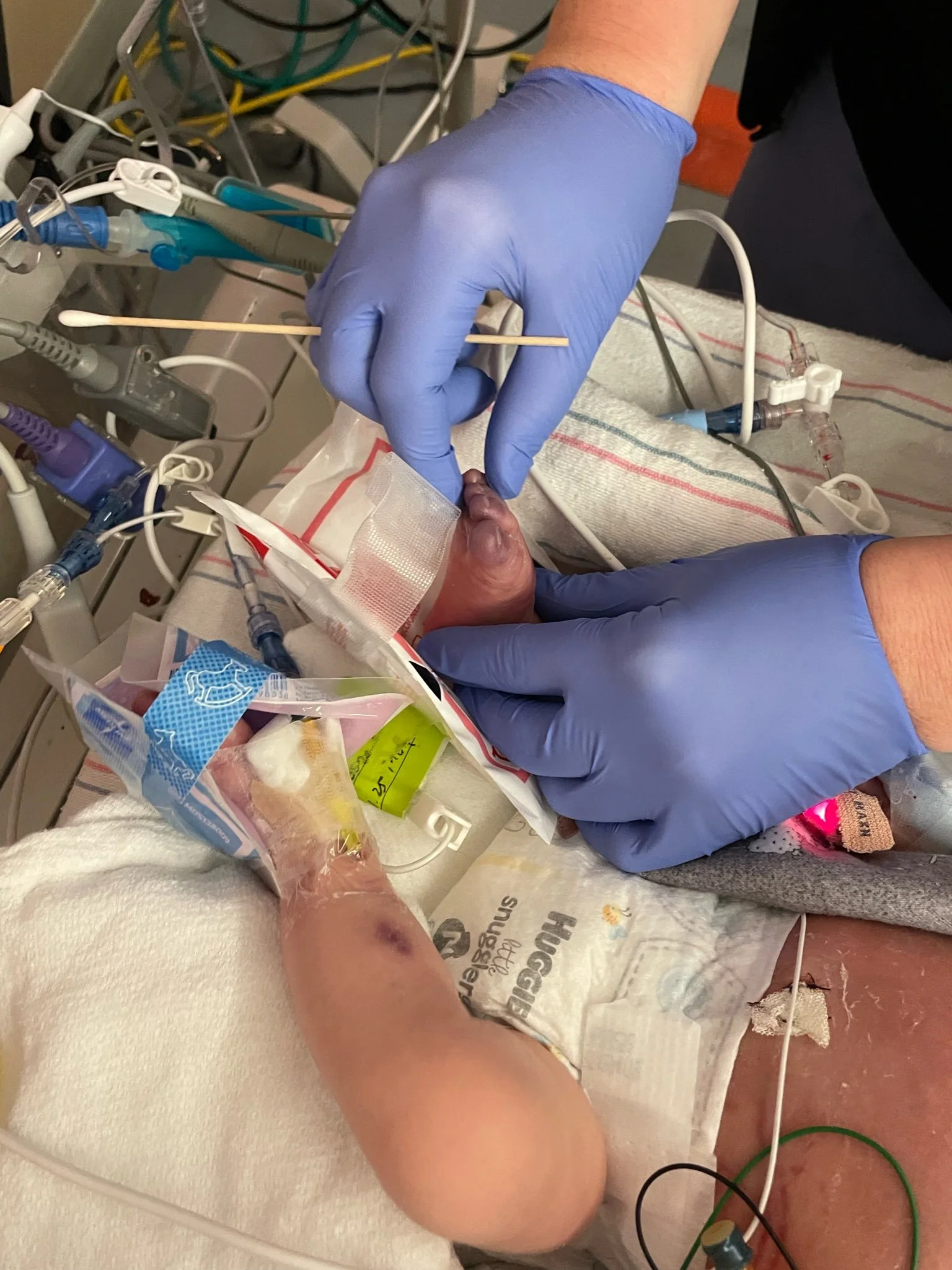

Because ECMO involves pumping and oxygenating your blood completely through a machine, they have to use blood thinners to keep the machine working properly. But blood doesn’t like to be outside the body and they were carefully looking for clots in the circuit. And those clots can break loose and cause problems. For Brighton, micro emboli, small blood clots, were getting stuck in her outer extremities, causing stress on her fingers and toes which began to look discolored from poor blood flow. The doctors were focused on her lungs and really could not do much about her fingers and toes while she remained on ECMO. The priority was getting her off ECMO. After expanding her set of machines to include dialysis to manage some fluid imbalances (she was now under the supervision of 3 full-time nurses), they began to see progress with her lungs on her x-rays. It was time to try and get her off of ECMO and move onto her CDH repair surgery.

Surgeons dramatically prefer to wait until babies can be taken off of ECMO to do surgery, as their blood is so thinned-out there’s a significant risk of bleeding. So, over the course of a few days, they tried to run Brighton’s ECMO support down very low to see how she responded, tweaking her pulmonary hypertension medication each time to see if it would help. But she just wasn’t ready to come off. This meant they needed to do her repair while still on ECMO. Without repairing the diaphragm and moving her organs back into place she might never be able to come off of ECMO. Not what we wanted to hear, but, we knew this might happen. Repair surgeries on ECMO are still relatively common for CDH patients that require this kind of support in the first place.

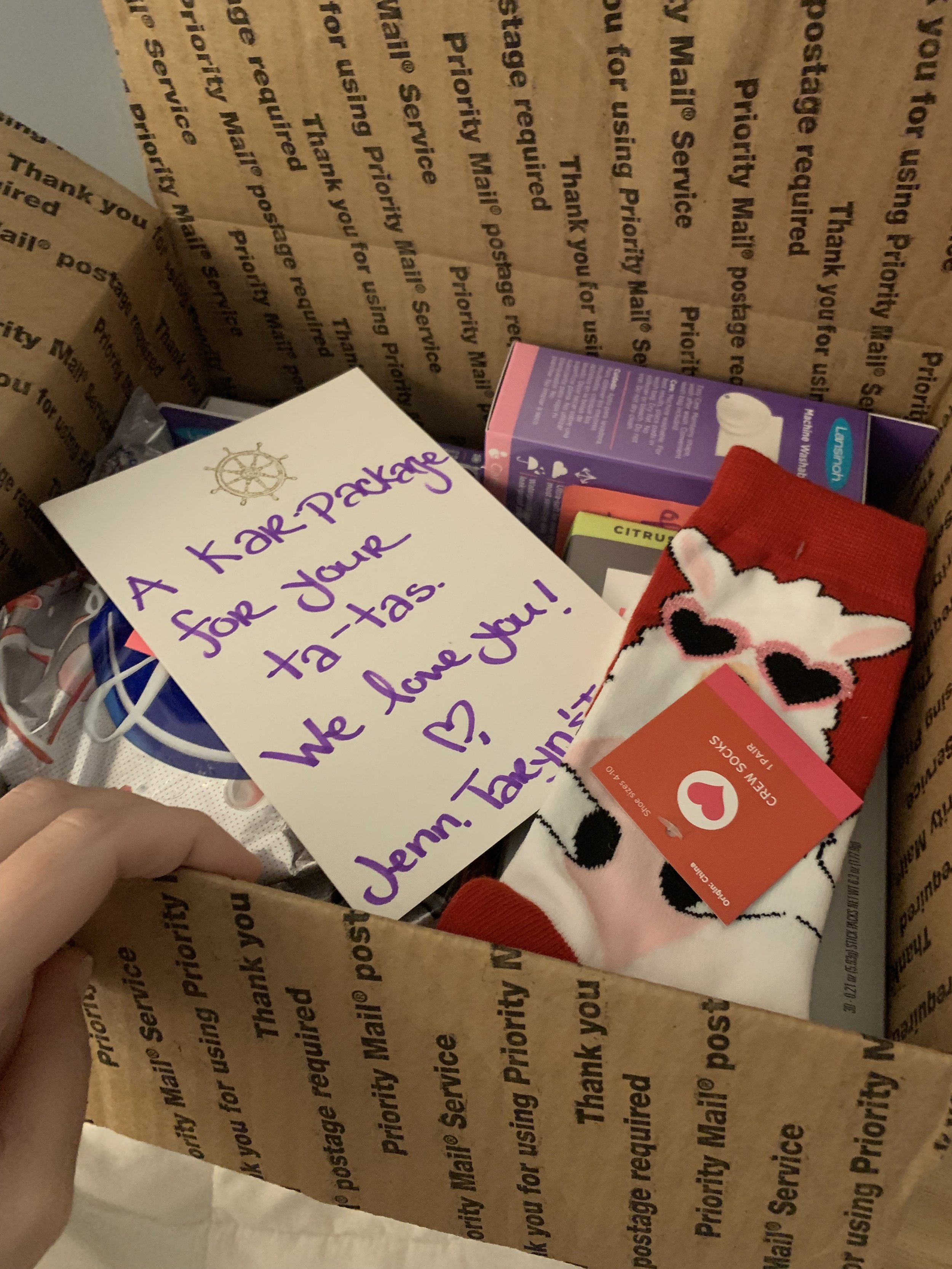

Surgery

In anticipation of the tough road ahead, Kari’s mom Judy and dear friend Denise Graves flew back in to Philadelphia to provide much needed support. Judy and Denise embroidered scent cloths and kept us company while we were away from the hospital trying to balance our anxiety with love and care.. As Brighton’s surgery approached, it was clear we were hitting a major inflection point. We had a great team and a world-class surgeon working on her, but she was incredibly sick. The picture of “success” was starting to become blurry, and even if she survived surgery and many more months in the hospital, the side effects and toll on her body was painful to see. She was expected to lose fingers and toes and have scars all over her body. They assured us she was not in pain, but as parents we knew the extent of what Brighton was going through and how it would impact her for years to come. At this point until Brighton’s passing about 9 days later, we barely left the hospital.

Brighton’s surgery took place on Thursday, February 3rd. We couldn’t stay with her as they need a sterile environment but were just down the hall in a small room. After a couple of hours, our surgeon and neonatologist came in to tell us the surgery went “as well as it could have,” but that Brighton’s bleeding was “profuse” and coming from “everywhere.” It was the first time the doctors seemed rattled by everything going on which was incredibly scary. Our Neonatologist told us she needed to get back to the bedside. Brighton was continuously receiving blood products and she just wouldn’t stop bleeding. They told us the next 24-48 hours would be tenuous. She was not stable. Surgery is hard on anyone, but this was a four-week old baby that was already very sick.

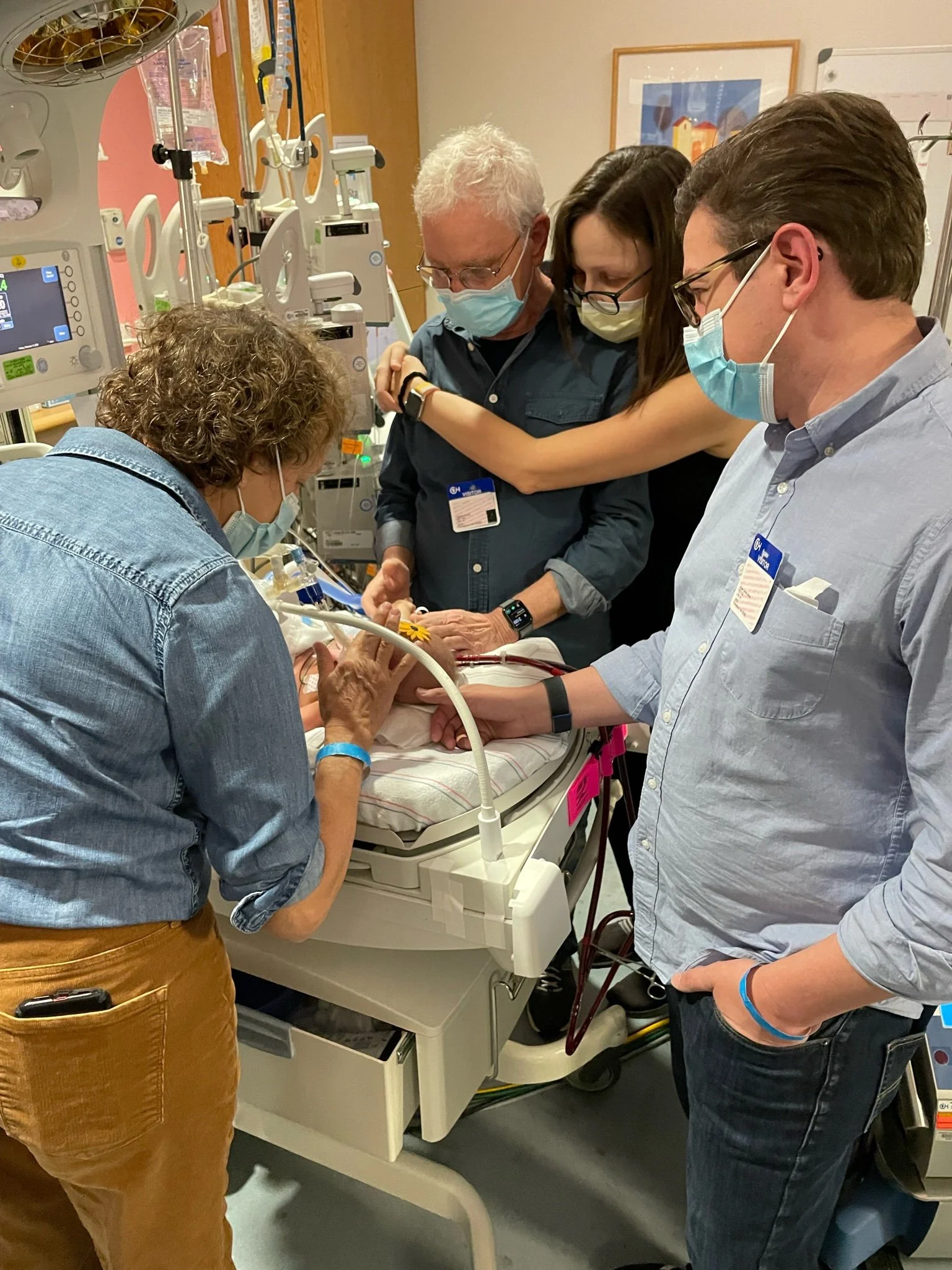

We hoped and prayed for the best. They eventually used an adult dose of Factor 7, a strong coagulant, which came with its own risks but they finally stopped the bleeding. Our mothers were both back in Philly and the hospital let them to come in to spend time with Brighton. After surgery she would swell up from excess fluid in her tissue and this was the most swollen she’d ever been. She was hard to the touch and her face and eyelids were so swollen that the tape holding her breathing tube looked like it was cutting into her skin and she had broken capillaries around her eyes. We were just barely holding it together. Kari was getting hives which had never happened before. These were some of the hardest and worst weeks of our lives. We continued to spend as much time as possible with Brighton, reading to her, holding her hand, touching her head, swapping out her bows and just being with her.

But each day presented us with a new problem. Her lungs had closed back up in response to the surgery (which was expected initially) and weren’t reopening to the degree they had been before surgery. Her coloring was off. They tried to take off more liquid with the Dialysis unit but she was cutting out more and they’d have to pull back. “Cutting Out” is when the ECMO circuit stops. This happens when they are trying to pull or push more blood in or out than the body can support at a certain pressure. When the pressure gets too high, the machine stops automatically to prevent damage and they have to pull back. We had been warned that parents have a really hard time with the swelling that happens but this seemed worse than normal.

Her toes were almost completely black and she had several fingers going in that direction. Everyone said there was nothing they could do but it was impossible to sit by and be like, “Okay, so she just won’t have fingers and toes.” Logically you can understand the importance of lung function over your hands and feet but having to repeatedly hear that it was the least of her issues was infuriating. Why weren’t more people coming to figure this out? Why weren’t people freaking out? How are they so resigned that there’s nothing they can do? Why is there a heat pack shortage? Kevin was ready to start buying them off Amazon before we were told they couldn’t accept outside products for the liability. I hadn’t really even understood why Plastics was the team who had recommended Nitro Paste and heat from the start until this point where we learned that they would be the team amputating her finger and toes which were dying before our eyes. They were pink and healthy and wiggling just days ago. When one of our surgeon’s matter of factly told me she would lose them, I fell into hysterics and couldn’t stop shaking my head. This cannot be happening to my darling baby. She needs her fingers. She needs her toes. How is this such a low priority?

We were living at the hospital at this point but we hadn’t brought enough clothing so we ducked away to pick up some essentials. While we were at Ronald McDonald, the surgeon called to let us know they had identified perforation in her bowels. With adult family members having had a burst appendix and ruptured bowel this past year, we knew how serious this was. If it can knock out an adult for months, what is it going to do to our dear baby? And yet again, the surgeons said that this was low on her priority list. Her bowels were contained in the silo and they could perform a procedure to cut out the damaged tissue and reattach to healthy tissue. In some ways, this felt like the beginning of the end. How can so many people list off critical organs as “lower priority”? She was so terribly sick that prioritizing anything else was a risk. I had learned about the valuation of human life and the breakdown of fingers, toes and limbs from and economics course around insurance claims but it only lets you wrap your head around the concept. There is nothing like stack ranking your baby’s body parts and coming to terms with which ones you can let go. I was so worried there wasn’t going to be any of her left after all of this.

Each day the bowels were looking worse. What started as a perforation progressed to necrosed tissue and there was more bad tissue than healthy present. And this is all just what we could see in the silo. Who knew what was going on inside of her. Her coloring continued to get more dark and dusky. They were having trouble with her IVs and had to place PICC lines in both of her legs to support her transfusion and medicine needs. We had joked early on that she was collecting medical devices and our little sweetheart had all but a few. Each IV change and medicine was a necessity but hurting her at the same time. Things were just getting worse and we couldn’t tell if they would get better. And we were getting even more attention from our doctors.

Our Last Days Together

On Tuesday, February 8, we had a “family meeting” scheduled with the full multidisciplinary team - surgery, neonatology, cardiology, psychology, social work, nursing… you name it. We expected it to be a presentation explaining Brighton’s go-forward course of treatment. Instead, it was essentially the two of us in front of about 15 people as the doctors told us that Brighton was likely not going to make it. The surgery was incredibly hard on her and along with her profusion issues, her lungs just did not have the vascular support to survive off of ECMO. They were going to see over the next couple of days what her progress was like and we would try again to get her off ECMO, but her chances were low and we should bring our families into town.

We held on to their words that they would try again. Throughout all of this, everyone had told us how resilient babies are and how they can surprise everyone. We knew it was going to go one way or another and our families planned their travel so that everyone would be together in Philadelphia by that Thursday. That morning, while Kevin, Elaine and Diana were spending time with Brighton, we received the terrible news that our dear dog Holly had passed away in the night. We were scared this was going to happen while we were gone but it only made everything worse. Thank you so much to our dear friend Neddi Yaeger for taking care of her in her final days and so much love and appreciate to my Aunt Judy and Uncle Jon for giving her such a loving burial at our family home.

That day our siblings, Bryan and Diana got to meet their niece for the first time and new grandfathers Alan and Dwight saw their first granddaughter. They were limiting the number of people at the bedside so many of these moments we missed as a family. But all in the name of safety and making sure her medical team had the appropriate access. We went to bed that night hoping that the ECMO support turn down over night would be successful and they would be able to try to turn off her ECMO for the last time in the morning.

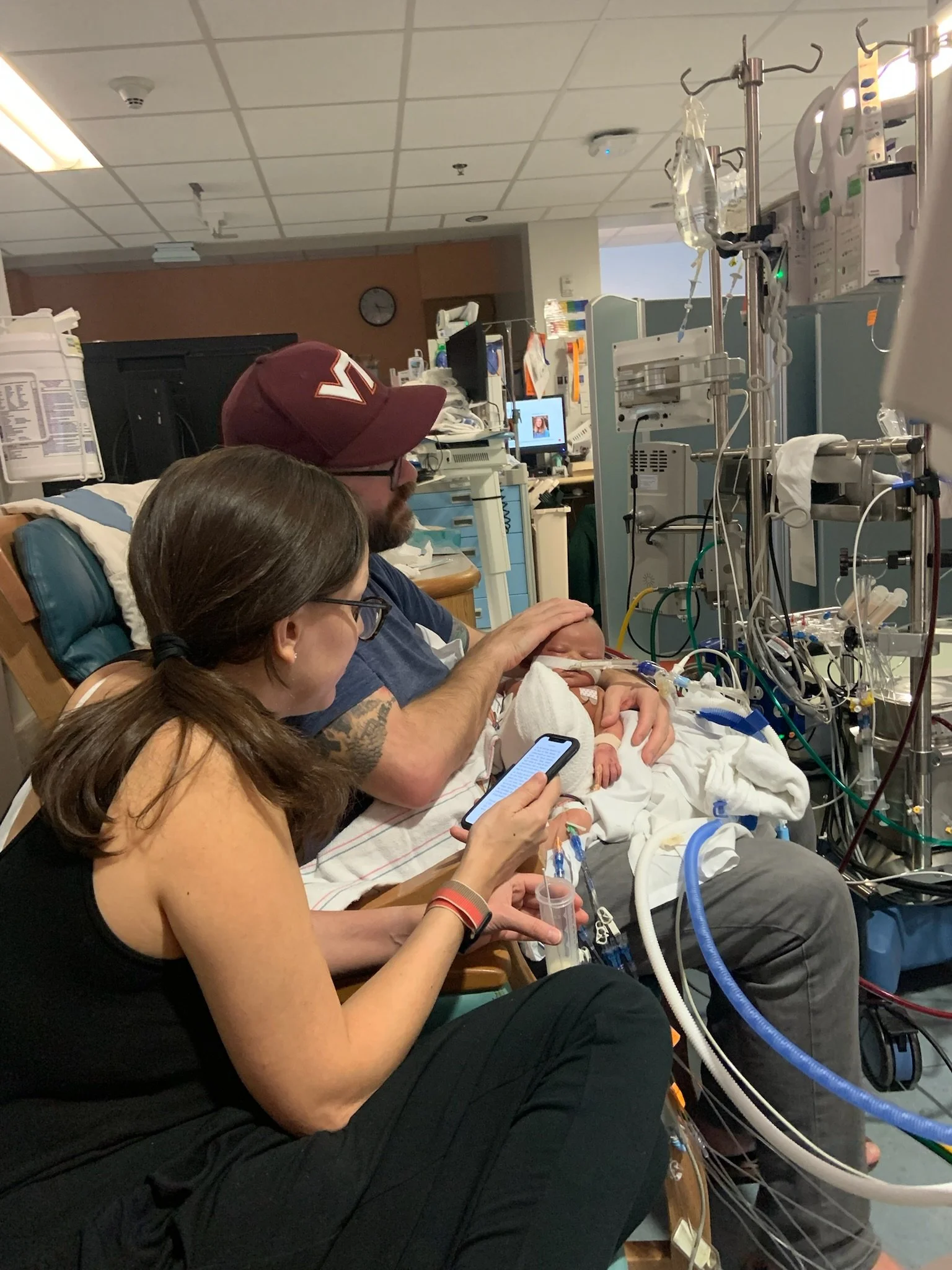

The next morning, we learned they had been able to reduce her ECMO support but not without other issues. They had had to increase some of her other medications to allow it and it wasn’t promising. Attempting a Turn Down Trial is a very involved intense process and they didn’t believe she would survive it. We spent the day with her as a family together with Brighton in the most heartbreaking, gut-wrenching experience of our lives. We finally got to hold her and discovered she was heavier than we expected. At 4 weeks and 6 days we’d never held her until this day. They’d increased her pain meds to make sure she was comfortable so she was very still. We sang to her and read books and told stories while the NICU buzzed around us.

Brighton passed away the evening of February 11, 2022 in Kari’s arms, surrounded by her grandparents Alan & Elaine Wade and Dwight & Judy Hiscox, her uncle Bryan Hiscox and her aunt Diana Wade. She fought so hard over her five weeks and we are incredibly proud of her. She went through so much and did everything she could but it was just too much. She is a hero and a treasure in our eyes. We’re so thankful for the time we have had with her and she has changed our lives forever.

We frankly didn’t even know how to leave the hospital after she had passed. We stayed with her until early in the morning and then slept at the hospital. Leaving in the morning we said goodbye to so many of the doctors and nurses that had fought so hard for her and truly are a part of her family. Even today it’s weird we’re not still in the NICU with her watching her vitals, chatting up the staff and just waiting for her to get better so we can go home.

There were so many people out there supporting us and Brighton and we can’t begin to thank you enough. From her medical team, to the volunteers at Ronald McDonald, to the prayer groups and friends and family near and far trying so hard for all of us. We’re heartbroken she didn’t make it and that we didn’t get to come back with good news. I’m so sorry that we couldn’t do that but so grateful for everything. Thank you.

There is so much more to Brighton’s story, and we’ll certainly be telling it here and hope to share it with all of you over time. It’s been heartbreaking every time we’ve had to let each of you know what’s happened, but Brighton is a part of all of our lives and we want all of you to know her like we have, which is as a wonderful girl full of life and personality and with so much to give to all of us.